“I don’t know if I’m optimistic but at least a conversation is starting.”

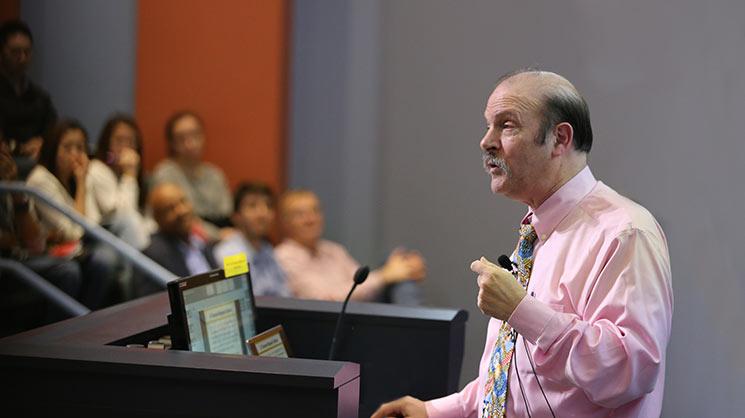

And Moshe Vardi further energized the conversation with his lecture, “An Ethical Crisis in Computing,” part of the Rice University Professor Lecture Series, held Jan. 22 in Duncan Hall. “It is not an ethical crisis in computing,” he said. “It is a failure in public policy.”

A University Professor and co-director of the Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology at Rice, Vardi reviewed the growing mood of public distrust, fear and anger prompted by high-tech security breaches, surveillance, the theft and sale of personal data, and interference in electoral politics. Vardi quoted the columnist Peggy Noonan who last year described Silicon Valley executives as “moral Martians who operate on some weird new postmodern ethical wavelength.”

“Academic institutions,” he said, “are launching new courses on computing, ethics and society. Others are taking a broader approach, integrating ethics across their computing curricula. The narrative is that what ails tech today is a deficit of ethics and the remedy, therefore, is an injection of ethics. This leaves me deeply skeptical. It is not that I am against ethics, but I am dubious of the diagnosis and the remedy.”

Vardi likened computing to another technology, the automobile. With it came an unintended consequence, traffic fatalities, which in most years since the 1970’s have declined. “It was not ethics training for drivers that was responsible. It was crash avoidance with mirrors. It was seat belts, anti-lock brakes, airbags, traffic lights and DWI laws. Public policy.”

High tech, he said, has little incentive to curb its worst practices. Google’s advertising revenues reached $95.4 billion in 2017. “How does Google make almost $100 billion from advertising?” Vardi asked. “Advertisers pay. Where do advertisers get the money? From consumers. Consumers pay for Google services, but in a totally opaque way. Mass surveillance!”

Vardi repeated: a scheme of ethics is not the answer. “The problem with surveillance capitalism,” he said, “is not that it is unethical, but that it is completely legal in many countries. It is unreasonable to expect for-profit corporations to avoid profitable and legal business models. The criticism of internet companies for ‘unethical’ business models is misguided. If society finds the surveillance business model offensive, the remedy is public policy in the form of laws and regulations, rather than an ethics outrage.”

Much of the outrage over high-tech malfeasance is naïve, Vardi said. He proposed the adoption of such measures as a plain language requirement for terms and licenses, laws obligating companies to quickly disclose data breaches, and requiring internet companies to provide an ad-free subscription option.

“Of course regulation chills innovation, “Vardi said. “The whole point of regulation is to chill certain kinds of innovation, the kind that public policy wishes to chill. At the same time, regulation encourages innovation. There is no question that automobile regulation increased automobile safety and fuel efficiency. Regulation can be a blunt instrument and must be wielded carefully. Otherwise, it can chill innovation in unpredictable ways. Public policy is hard, but it is better than anarchy.”

Vardi announced a new Rice initiative devoted to “technology, culture and society.” “It will study how technology impacts society and culture, and how society should respond to such an impact,” he said. “It will have three legs: research and scholarship, education, and outreach.”

Patrick E. Kurp, Science Writer, George R. Brown School of Engineering