“My work is at the intersection of immunology, computer science and biochemistry and one of the greatest challenges to explaining the research is to NOT go into the background of these disciplines,” said Dinler Antunes. “You have to dive right into the heart of the problem using language that broad audiences understand.

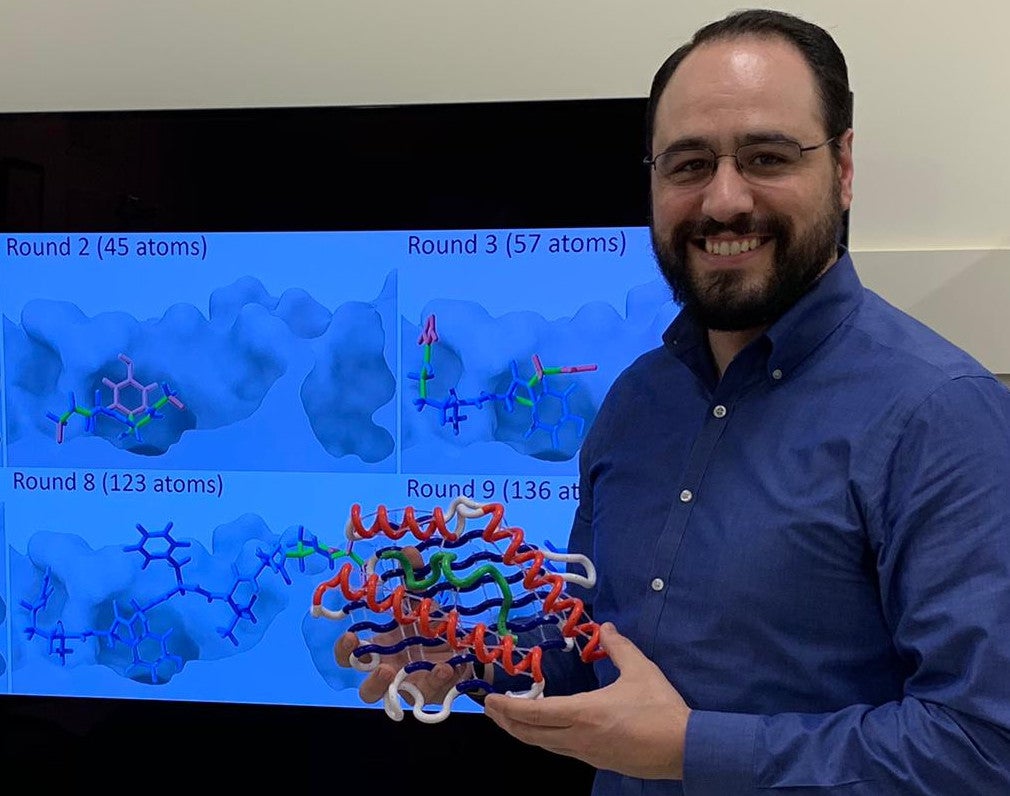

“In my case, the key message is that cancer is a challenging problem in the medical field and immunotherapy can leverage the immune system of the patient to find and eliminate cancer cells. My work focuses on analyzing the molecules involved in identifying cancer cells, and how to enhance the immune response without triggering dangerous toxicities.”

Now an assistant professor of Computational Biology at the University of Houston, Antunes learned methods to improve his research communication while completing a postdoctoral fellowship with Lydia Kavraki at Rice University. Halfway through his appointment, Antunes was selected as one of the first Future Faculty Fellows (FFF) at Rice’s George R. Brown School of Engineering.

The FFF training included workshops by Tracy Volz and Chris Lipp in Rice’s ACTIVATE engineering communication program. Volz focused on written communication and Lipp tackled oral presentations. Antunes said, “I was in a bit of a hurry, because I had already begun applying for faculty jobs. Both Tracy and Chris gave me tips, and helped me make small changes that had a huge impact on the success of my applications, correspondence, and interviews.

“When it comes to talking about science and technology, it is hard to give up the language we’ve learned in our years of research. We are trained as Ph.D. students to use terms that specify the exact problem and solution we are exploring. But that is counter-productive when you are talking to a broader audience.”

Antunes believes the difficulty of sharing complicated scientific issues and breakthroughs with the general public is one of the contributing factors to confusion about the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccinations. But it can be just as challenging to share research updates with colleagues as with the public.

“In academic departments, each of us works in a niche and our colleagues are focused in other specialty areas. We don’t always share the same vocabulary and references. Talking about our work in more general terms rather than technical jargon allows more people to gain insight into the research,” said Antunes.

Engineers and scientists who want to share complex information must quickly engage their audience and continually adapt their message in order to keep their audience’s attention. Already familiar with biomedical talks, Antunes was surprised at the early feedback on his oral presentations in the FFF workshops.

“I volunteered to be the first presenter because I was already confident of my talk,” said Antunes. “We only had to give a five minute pitch in the workshop, but Chris stopped me after three sentences. He told me it was boring and he had no idea what I was talking about.

“Rather than introduce myself and slowly build up the details of my research, I had to learn to tell the audience why it mattered, and spend the first part of the talk working to capture their attention. In the writing workshop, Tracy provided similar feedback. In my cover letter, I learned to not start with details of my research, but to explain why I was a good match for their department. These are a few of the changes the ACTIVATE team prompted in my communication skills.”

Antunes was a quick study. He made immediate changes to his communication style in both his job search and in his approach to seminars. Those improvements resulted in an offer from his first choice employer and an award at a prestigious conference.

“The Immuno-Oncology Young Investigators’ Forum is a selective, national conference. Young researchers must submit a project and CV to be selected for the forum, and finalists give a brief talk that is judged by senior researchers during the conference. It is challenging to distill years of research into a short talk, but thanks to the FFF training, I was prepared to quickly focus on the necessary details and what matters most. At the end of the forum, I was one of three postdocs recognized for giving the best talk.”

That success did not convince Antunes to coast. He continues working to improve both his presentations and his written communications, including research papers and his website. Antunes believes even grant proposals benefit from opening with a bird’s-eye view.

“We want to say and write things in a very complicated and precise manner, but when we read the work of others we want to quickly grasp the concepts and understand them. The papers with the broadest impact are those that manage to convey the bigger picture and how this specific research supports it. Reaching more people, achieving more collaboration —these are the benefits of learning to write at a more general level,” he said.

His approach to generate funding and attract graduate students to his research team in the University of Houston Department of Biology and Biochemistry relies on Antunes’ improved communication. He said his efforts at grant writing and engaging students are more successful when both audiences understand the big picture, since the long term goal may take years to achieve.

“Once the funding agencies and the students understand the long term benefits, it is easier to convince them to undertake the short term objectives. Even if the ground-based work involves tasks that are repetitive or tedious, knowing how it fits into the long term goal allows them to feel more engaged. Give them something to visualize and they are more likely to buy into why it is important to get this part done well, right now.

“It is exciting to be creating my own group and establishing my own line of research at the University of Houston, from writing grant proposals to finding new collaborations. And attracting new grad students to a computational lab focused on cancer immunotherapy means devising interesting projects that are engaging and not too difficult, but still push my own research forward. And of course, those projects have to be negotiated with the students. A project I think is perfect for them might not click and we'll need to find a compromise.”

Antunes fully expects to model clear communication with the graduate students he advises, but he also wants to mentor them as they write and give talks. He said students are often eager to show everything they know into each email, paper, or presentation.

“The message I try to relate to them is ‘less is more.’ Control your anxiety. Dumping everything you know on the audience will shut them down. Convey the big picture and highlights. When the audience expresses interest, then you can dive deeper. And that’s how you can successfully convey the importance of your work."